Seminar 1

Exercise 1, Difficulty 1

Two identical coins each have a ‘0’ on one side and a ‘1’ on the other. Both coins are tossed, and the sum of the numbers showing is calculated. This process is then repeated. What is the probability that the same sum is obtained on both tosses, under the following conditions:

- the coins are distinguishable.

- the coins are indistinguishable (bosonic).

Let \(S_1, S_2\) be the sum of the first and second tossing. We need to find \(\mathbb{P}(S_1=S_2) = \sum_{k=0}^2 \mathbb{P}(S_1=k)^2\).

For distinguishable coins, the sample space is \(\{(0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1)\}\), with each outcome having probability \(1/4\). The probabilities for the sums are \(\mathbb{P}(S=0)=1/4\), \(\mathbb{P}(S=1)=1/2\), \(\mathbb{P}(S=2)=1/4\). \(\mathbb{P}(\text{same sum}) = (1/4)^2 + (1/2)^2 + (1/4)^2 = 6/16 = 3/8\).

For indistinguishable (bosonic) coins, the sample space is the set of outcomes \(\{\{0,0\}, \{0,1\}, \{1,1\}\}\). Assuming these are equally likely, each has probability \(1/3\). The probabilities for the sums are \(\mathbb{P}(S=0)=1/3\), \(\mathbb{P}(S=1)=1/3\), \(\mathbb{P}(S=2)=1/3\). \(\mathbb{P}(\text{same sum}) = (1/3)^2 + (1/3)^2 + (1/3)^2 = 3/9 = 1/3\).

Exercise 2, Difficulty 1

You are taking an exam along with other students. The number of students is equal to the number of exam tickets, which is \(n\). It is known that among the tickets, there are \(1\le k\le n\) easy ones. Students enter the room one by one, draw a ticket, and keep it. When is the best time for you to enter to maximize the probability of drawing an easy ticket? To figure out this burning question, calculate the probability of drawing an easy ticket if you enter

- first;

- \(j\)-th, \(1\le j \le n\).

By symmetry (permutation invariance of the probability of each sequence of easy/hard problems), the probability is independent of the position.

- For the first student, the probability is clearly \(k/n\).

- Any of the \(n\) tickets is equally likely to be in the \(j\)-th position. Since \(k\) of them are easy, the probability is \(k/n\). The time of entry does not matter.

Exercise 3, Difficulty 3

Consider a random placement of \(n\) indistinguishable (bosonic) particles into \(M\) distinguishable cells. Calculate the probability \(Q_k (n; M)\) that a fixed cell contains \(k\) particles.

Find the limit of \(Q_k (n; M)\) as \(n, M \to \infty\) such that \(n/M \to \lambda\), where \(\lambda>0\) is fixed.

Note: This distribution is called “Bose-Einstein statistics”; it describes the distribution of bosons over energy levels and provides a physical justification for a model where indistinguishable items are placed in distinguishable containers.

The total number of configurations is \(\binom{n+M-1}{n}\). If we fix one cell to have \(k\) particles, we must distribute the remaining \(n-k\) particles into the other \(M-1\) cells. The number of ways is \(\binom{(n-k)+(M-1)-1}{n-k} = \binom{n-k+M-2}{n-k}\). \[ Q_k(n; M) = \frac{\binom{n-k+M-2}{n-k}}{\binom{n+M-1}{n}} \]

In the limit, this probability converges to a geometric distribution with parameter \(p = \frac{\lambda}{\lambda+1}\). \[ \lim_{n,M\to\infty} Q_k(n;M) = (1-p)p^k = \frac{1}{\lambda+1}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\lambda+1}\right)^k \]

Exercise 4, Difficulty 2

There is a code of length \(n\) consisting of digits from \(0\) to \(9\). Find the probability that the digits are arranged in non-decreasing order.

The total number of codes is \(10^n\). A non-decreasing sequence is determined by the multiset of its digits. The number of such multisets of size \(n\) from 10 digits is \(\binom{n+10-1}{n} = \binom{n+9}{n}\). \[ \mathbb{P}(\text{non-decreasing}) = \frac{\binom{n+9}{n}}{10^n} \]

Exercise 5, Difficulty 1

From a deck (52 cards), 4 cards are drawn.

- What is the probability that all 4 cards are spades?

- What is the probability that 3 cards are spades and one is a heart?

Recall that a French deck (poker deck) of \(52\) cards is composed by \(4\) suits, each one counting \(13\) kinds (or values).

There are \(\binom{52}{4}\) ways to sample \(4\) cards out of \(52\). There are \(\binom{13}{4}\) to sample spade cards. So the probability is \(\frac{\binom{13}{4}}{\binom{52}{4}}=\frac{13! 48!}{52! 9!}=\frac{13 \cdot 12 \cdot 11 \cdot 10}{52 \cdot 51 \cdot 50 \cdot 49}\approx 0.0026\).

There are \(\binom{13}{3} \binom{13}{1}\) ways to choose \(3\) spade cards and one heart card. So the answer is \(\frac{\binom{13}{3} \binom{13}{1}}{\binom{52}{4}}\approx 0.0137\).

Exercise 6, Difficulty 3

There are three numbered boxes \((1,2,3)\). \(10\) indistinguishable (bosonic) white balls and \(4\) numbered red balls \((1,2,3,4)\) are randomly distributed among them. Find the probability that each box contains at least one white ball and at least one red ball with a number greater than the box number.

The placements of white and red balls are independent.

- White Balls: There are \(\binom{10+3-1}{10}=66\) way to distribute \(10\) indistinguishable balls into \(3\) boxes. Ways with at least one in each box is \(\binom{10-1}{3-1}=\binom{9}{2}=36\). So \(p_W = 36/66 = 6/11\).

- Red Balls: Total ways to place \(4\) distinguishable balls is \(3^4=81\). The condition requires \(R_2\) in Box 1, \(R_3\) in Box 2, and \(R_4\) in Box 3. \(R_1\) can be in any of the \(3\) boxes. This gives \(3\) favorable placements. So \(p_R = 3/81 = 1/27\).

By independence the answer is \(p_W p_R = \frac{6}{11} \times \frac{1}{27} = \frac{2}{99}\).

Exercise 7, Difficulty 3

There are three boxes, containing three black and three white balls randomly placed. Find the probability that the first box contains at least two black balls, and the third box contains no more than one white ball, if

- the balls are numbered

- the balls are distinguished only by color (bosonic).

Let A be the event for black balls and B be for white balls. The events are independent.

-

Numbered balls: Total ways for each color is \(3^3=27\).

- \(\mathbb{P}(A)\): Favorable ways for \(B_1 \ge 2\) is \(\binom{3}{2} \cdot 2^1 + \binom{3}{3} \cdot 2^0 = 7\). So \(\mathbb{P}(A)=7/27\).

- \(\mathbb{P}(B)\): Favorable ways for \(W_3 \le 1\) is \(2^3 + \binom{3}{1} \cdot 2^2 = 20\). So \(\mathbb{P}(B)=20/27\).

- \(\mathbb{P}(A \cap B) = \mathbb{P}(A)\mathbb{P}(B) = \frac{7}{27} \frac{20}{27} = \frac{140}{729}\).

-

Bosonic balls: Total ways for each color is \(\binom{3+3-1}{3}=10\).

- \(\mathbb{P}(A)\): Configurations \((b_1,b_2,b_3)\) for \(b_1 \ge 2\) are \((2,1,0), (2,0,1), (3,0,0)\). 3 favorable ways. \(\mathbb{P}(A)=3/10\).

- \(\mathbb{P}(B)\): Configurations for \(w_3 \le 1\): (4 with \(w_3=0\)) + (3 with \(w_3=1\)) = 7 ways. \(\mathbb{P}(B)=7/10\).

- \(\mathbb{P}(A \cap B) = \mathbb{P}(A)\mathbb{P}(B) = \frac{3}{10} \frac{7}{10} = \frac{21}{100}\).

Exercise 8, Difficulty 2

There is a box with 30 distinguishable balls, of which 10 are red and 20 are black. 12 balls are drawn at random (without regard to order and without replacement). Find the probability that among the drawn balls, there is an equal number of red and black ones. What changes if the order is taken into account?

We need the probability of drawing 6 red and 6 black balls.

- Without order: The probability is given by \(\mathbb{P}(\text{6R, 6B}) = \frac{\binom{10}{6} \binom{20}{6}}{\binom{30}{12}} \approx 0.0941\).

- With order: Nothing changes. Just an extra \(12!\) in the numerator and denominator.

Exercise 9, Difficulty 3

This is how a (one-dimensional) transmission line of a cellular network works. \(n\) antennas are arranged in a line at equal distances. Each antenna repeats the signal received from the neighboring antenna. The signal can travel a distance of two antennas, so the transmission works if there are no two consecutive faulty antennas. Suppose that \(m < n\) antennas are faulty, but we do not know their positions. What is the probability that the transmission works?

- \(\mathrm{I I X I I I X I}\) = works

- \(\mathrm{I I X X I I I I}\) = does not work

Mark a ‘I’ for a functional antenna, and a ‘X’ for a non-functional one. To identify a configuration of working-nonworking antennas, it is enough to give the position of the \(m\) ’X’s, out of the \(n\) possible positions. So we have \(\binom{n}{m}\) equally likely possibilities.

How many of them do not have two consecutive ‘\(\mathrm{X}\)’s? To calculate, draw the following picture: \[ \mathrm{\_ \,I \,\_ \,I \,\_ \,I \ldots \_ \,I\, \_} \] where there are \((n-m)\) ’I’s. To produce a functional configuration, we can put the \(m\) non-functional antennas in any of the \(n-m+1\) free spots marked with’_’. So the probability of having a working network is \[ \frac{\binom{n-m+1}{m}}{\binom{n}{m}} \] which of course means \(0\) for \(2m > n+1\).

Exercise 10, Difficulty 3

A person flips a coin repeatedly. They stop as soon as they get a sequence of \(n\) heads or a sequence of \(1\) tail and \((n-1)\) heads in a row.

- What is the probability that they will stop?

- What is the probability that they will stop at a sequence of n heads?

The person will stop with probability 1.

There is only one way they can see a sequence of \(n\) consecutive heads, before \(1\) tail and \((n-1)\) heads: this sequence appears right at the beginning. So the required probability is \(2^{-n}\). In general, given two sequences of heads and tails (or \(0\) and \(1\)), it is hard to calculate exactly the probability that one appears before the other. Certainly, it does not depend only on the length of the sequence, as this exercise readily shows.

Exercise 11, Difficulty 4

An electric train consists of \(n\) cars. Each of \(k\) passengers chooses a car at random. What is the probability that every car will have at least one passenger? What is the probability that exactly \(r\) cars will be occupied?

If \(E\) is the set of passengers and \(F\) the set of wagons, the exercise is reduced to calculating some combinatorics of functions \(f\colon E\to F\) (assignments of passengers into wagons). Since \(|E|=k\) and \(|F|=n\), there are \(n^k\) total functions \(f\colon E \to F\).

Here we need to calculate how many surjective functions \(f\colon E\to F\) there are. Assume \(k\ge n\) (otherwise the answer is \(0\)). For \(A\subset F\), define \[ \text{Number of functions with image in } A = |A|^k \] By the principle of inclusion-exclusion, the number of functions having exactly \(F\) as an image is: \[ \text{Number of surjective functions} = \sum_{j=0}^n (-1)^{n-j} \binom{n}{j} j^k \] To find the probability, just divide by \(n^k\).

We need to calculate how many functions have an image of cardinality \(r\). First, we choose the \(r\) cars that will be occupied in \(\binom{n}{r}\) ways. Then, we count the number of surjective functions from the \(k\) passengers to these \(r\) cars. From the previous part, this is \(\sum_{j=0}^r (-1)^{r-j}\binom{r}{j}j^k\). The total number of ways is: \[ \binom{n}{r} \sum_{j=0}^r (-1)^{r-j}\binom{r}{j}j^k = \sum_{j=0}^r (-1)^{r-j}\binom{n}{n-r,r-j,j} j^k \] Divide by \(n^k\) for the probability.

Exercise 12, Difficulty 4

Passengers on a bus take their seats randomly, ignoring the seat numbers on their tickets. The number of passengers is equal to the number of seats. What is the probability that none sits in their assigned seat?

Let \(n\) be the number of passengers and seats. The total number of permutations is \(n!\). We want to count permutations with no fixed points. Let \(A_i\) be the set of permutations where passenger \(i\) is in the correct seat. We want to find \(n! - |\cup_{i=1}^n A_i|\). By the principle of inclusion-exclusion: \[ |\cup_{i=1}^n A_i| = \sum_{i} |A_i| - \sum_{i<j} |A_i \cap A_j| + \dots + (-1)^{n-1} |A_1 \cap \dots \cap A_n| \] The size of the intersection of \(k\) such sets is the number of permutations where \(k\) specific passengers are in their correct seats, which is \((n-k)!\). There are \(\binom{n}{k}\) such intersections. \[ |\cup_{i=1}^n A_i| = \sum_{k=1}^{n} (-1)^{k-1} \binom{n}{k} (n-k)! = \sum_{k=1}^{n} (-1)^{k-1} \frac{n!}{k!} \] The number of derangements is \(D_n = n! - |\cup_{i=1}^n A_i| = n! - \sum_{k=1}^{n} (-1)^{k-1} \frac{n!}{k!} = n! \sum_{k=0}^{n} \frac{(-1)^k}{k!}\). The probability is: \[ \mathbb{P}(\text{no one in correct seat}) = \frac{D_n}{n!} = \sum_{k=0}^{n} \frac{(-1)^k}{k!} \] As \(n \to \infty\), this probability converges to \(e^{-1}\).

Exercise 13, Difficulty 3

A person bought two boxes of matches at the same time and put them in his pocket. After that, every time he needed to light a match, he randomly took one box or the other. After some time, upon taking out one of the boxes, the person found it to be empty. What is the probability that the other box at that moment contained \(k\) matches, if the number of matches in a new box is \(n\)?

To fix the notation, let’s say that at the beginning there were \(n\) matches in each pocket. Let’s calculate the probability that the person finds the right pocket empty, and that at this moment there are \(k\) matches in the left pocket. For this to happen, they must choose the right pocket \(n\) times out of \(n+(n-k) = 2n-k\) tries, and then they must choose the right pocket yet again at the \((2n-k+1)\)-th try. The number of such sequences of choices is \(\binom{2n-k}{n}\). Each sequence has probability \((1/2)^{2n-k+1}\). Thus this probability equals \(\binom{2n-k}{n} (\frac{1}{2})^{2n-k+1}\). The required probability is then \(\binom{2n-k}{n} 2^{-(2n-k)}\), since the left pocket may also be the first one to get empty.

Exercise 14, Difficulty 3

Using a random selection scheme with replacement from the set of natural numbers \(\{1,\dots,N\}\), \(N\ge 2\), the numbers \(\xi\) and \(\eta\) are chosen (in other words all the \(N^2\) pairs \((i,j)\) have the same probability). Show that \[ \mathbb{P}\left(\xi^2-\eta^2 \text{ is divisible by 2}\right) < \mathbb{P}\left(\xi^2-\eta^2 \text{ is divisible by 3}\right) \]

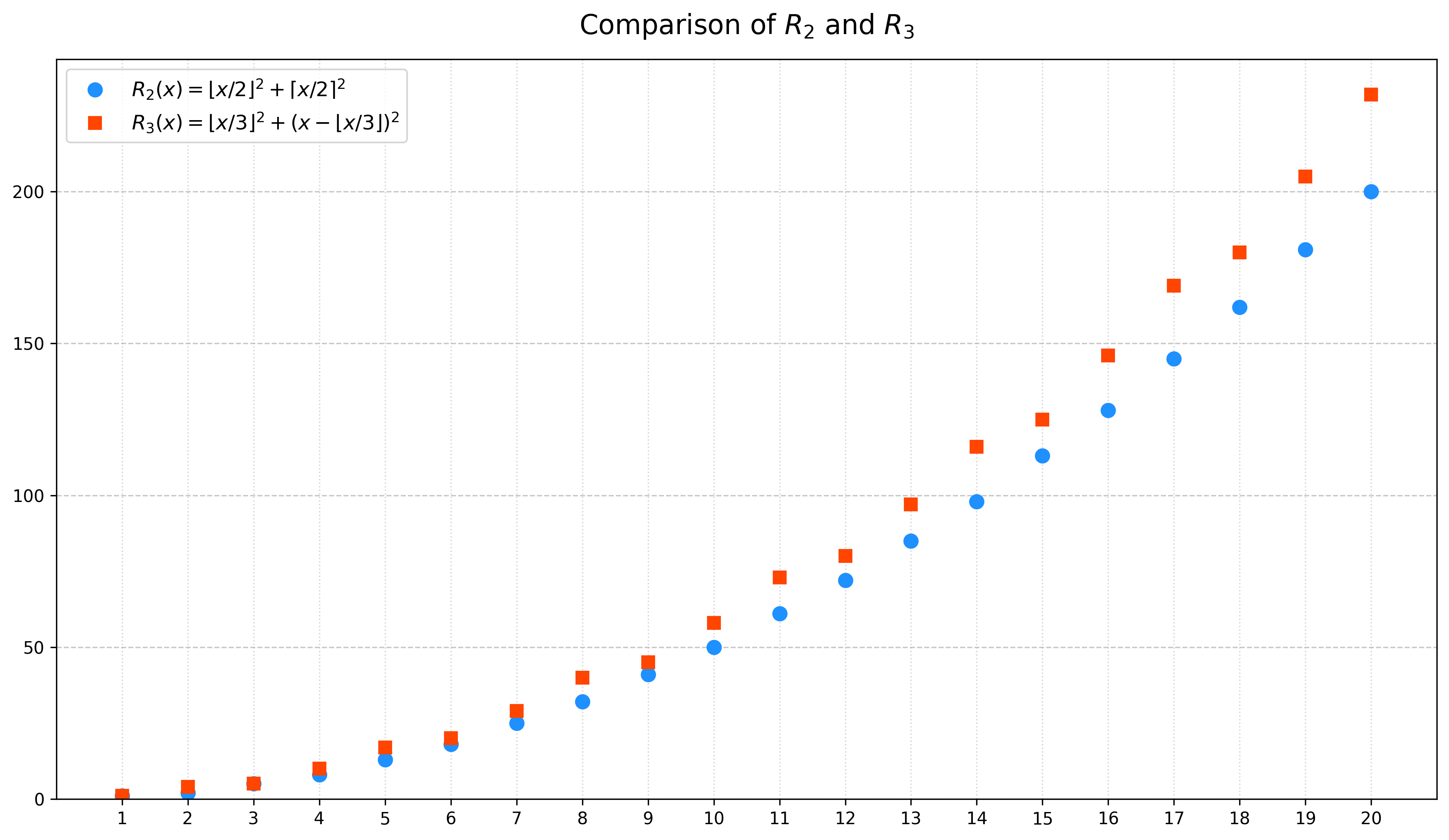

Let \(R_k\) be the number of pairs \((i,j)\), \(1\le i,j \le N\), such that \(i^2=j^2 \pmod k\). We need to prove that \(R_2 < R_3\), since the probabilities are obtained dividing both sides by \(N^2\).

- Divisibility by 2: \(i^2-j^2 = (i+j)(i-j)\) is divisible by \(2\) iff \(i\) \(j\) are either both even or both odd. So \(R_2= (\lfloor N/2 \rfloor)^2 + (\lceil N/2 \rceil)^2\).

- Divisibility by 3: For an integer \(z\), \(z^2 \pmod 3\) can be either \(0\) or \(1\). So \(3\) divides \(\xi^2-\eta^2\) iff \(\xi, \eta\) are both divisible by 3 or both not. Thus \(R_3= \lfloor N/3 \rfloor^2 + (N - \lfloor N/3 \rfloor)^2\).

- For \(N\) large, \(R_2 \simeq N^2/2\) and \(R_3\simeq 7 N^2/9\) so clearly the inequality holds for \(N\) large enough. With some elementary analysis, we see that it holds for \(N\ge 2\).

Exercise 15, Difficulty 4

Using a random selection scheme with replacement from the set of natural numbers \(\{1,\dots,N\}\), \(N\ge 3\), numbers \(\xi\) and \(\eta\) are chosen. Which is greater, \(\mathbb{P}\left(\xi^3+\eta^3 \text{ is divisible by 3}\right)\) or \(\mathbb{P}\left(\xi^3+\eta^3 \text{ is divisible by 7}\right)\)?

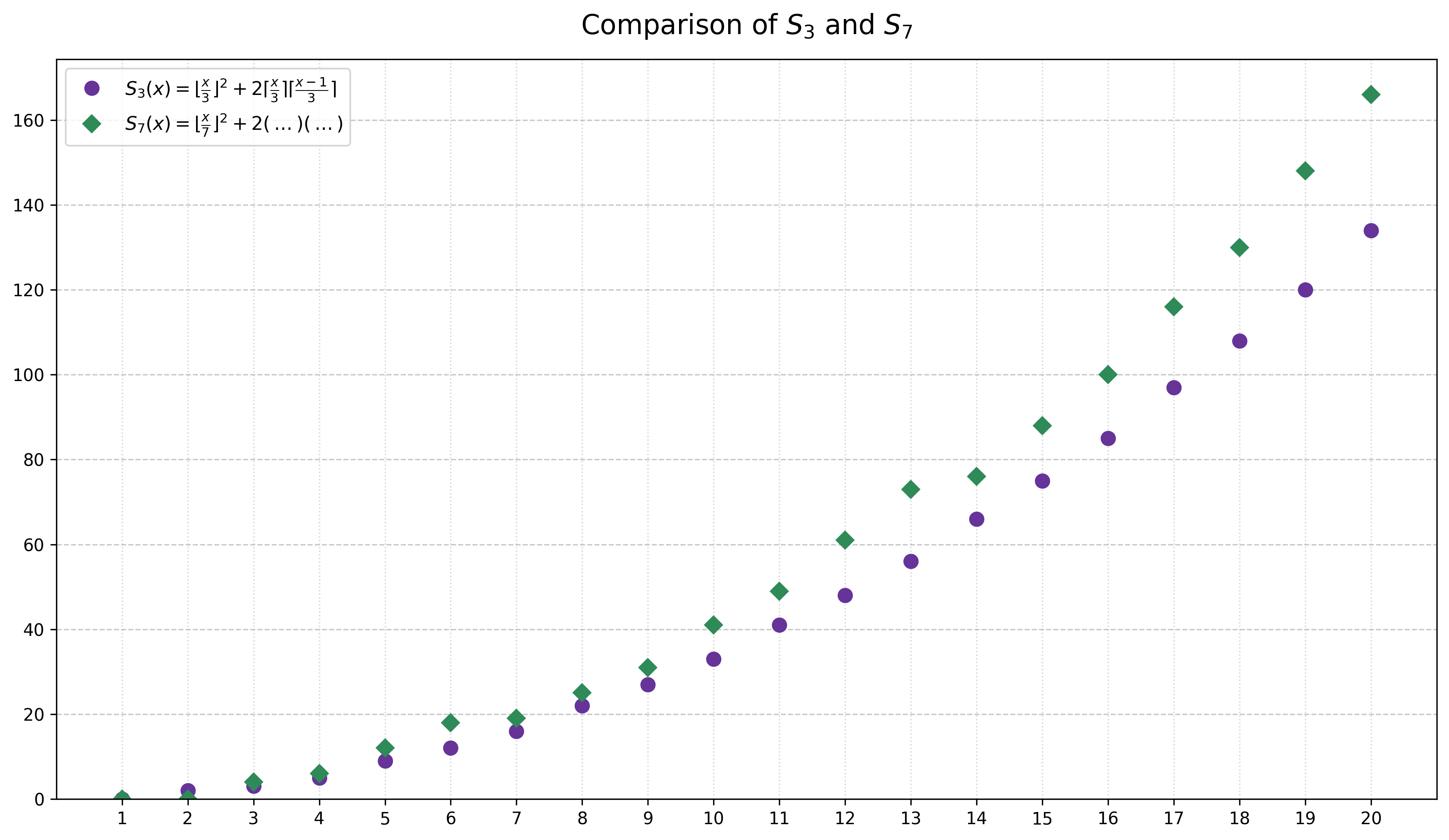

Let \(S_{k} := N^2 \mathbb{P}(\xi^3+\eta^3 = 0 \pmod k)\) be the number of pairs \((i,j)\) such that \(i^3+j^3 = 0 \pmod k\), with \(1 \le i,j\le N\).

- Divisibility by 3: The cubic residues of \(x^3\) are \((0^3,1^3,2^3)=(0,1,2) \pmod 3\) (which is just Fermat little Theorem \(x^p=x \pmod p\)). Thus \(\xi^3+\eta^3 = \xi+\eta \pmod 3\) is \(0 \pmod 3\) iff: both \(\xi\) and \(\eta\) are divisible by \(3\), or one has residue \(1\) and the other \(2\). Thus \[ S_{3}= \lfloor N/3 \rfloor^2 + 2 \lceil N/3 \rceil * \lceil (N-1)/3 \rceil \]

- Divisibility by 7: The cubic residues \(\pmod 7\) are \((0^3, 1^3, \dots, 6^3) = (0, 1, 1, 6, 1, 6, 6) \pmod 7\). So \(\xi^3+\eta^3 = 0\pmod 7\) iff both \(\xi\) and \(\eta\) are divisible by \(7\), or one has residue \(1\) and the other \(6\). Thus \[ S_{7}= \lfloor N/7 \rfloor^2 + 2 \left( (\lceil N/7 \rceil + \lceil (N-1)/7 \rceil+ \lceil (N-3)/7 \rceil ) (\lceil (N-2)/7 \rceil + \lceil (N-4)/7 \rceil + \lceil (N-5)/7 \rceil) \right) \]

- For \(N\) large, \(S_3 \simeq N^2/3\), \(S_7 \simeq 19 N^2/49\). so clearly the inequality holds for \(N\) large enough. With some elementary analysis, we see that it holds for \(N\ge 3\).

Exercise 16, Difficulty 5

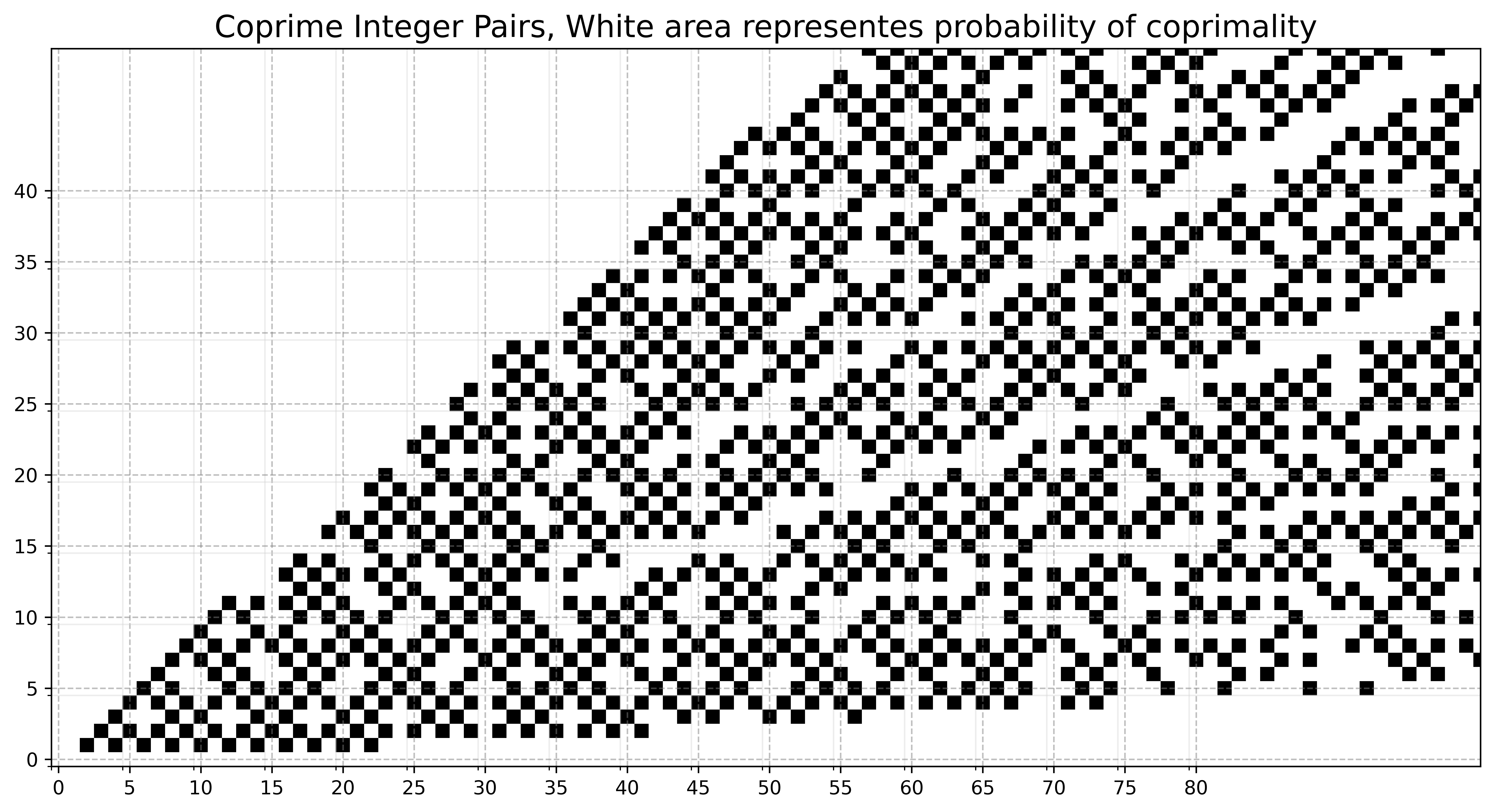

The random numbers \(\xi\) and \(\eta\) are chosen independently and uniformly in \(\{1,\dots,N\}\). Find the probability \(q_N\) that \(\xi\) and \(\eta\) are coprime. Find \(\lim_{N\to\infty}q_N\), interpreted as the probability that two numbers are coprime.

Let \(q_N = \mathbb{P}_N(\mathrm{gcd}(\xi,\eta)=1)\). \(A_p\) be the event “\(p\) divides \(\xi\)”, \(B_p\) the event “\(p\) divides \(\eta\)”. Then \[ q_N = \mathbb{P}_N\left( \cap_{p \text{ prime}} (A_p \cap B_p)^c \right) \] Now, as \(N\) becomes large, we can informally infer that \((A_p \cap B_p)\) and \((A_{p'} \cap B_{p'})\) become \(\mathbb{P}_N\)-independent, while \(A_p\) and \(B_p\) are independent (exactly) for each \(N\). So the previous formula gives \[ \begin{aligned} q_N & \simeq \prod_{p \text{ prime}} \mathbb{P}_N\left((A_p \cap B_p)^c \right)= \prod_{p \text{ prime}} 1- \mathbb{P}_N(A_p)^2 \\ & \simeq \prod_{p \text{ prime}} (1-1/p^2)= \left( \prod_{p \text{ prime}} \frac{1}{1-p^{-2}}\right)^{-1} = \left( \sum_{n\ge 1} \tfrac{1}{n^2}\right)^{-1}= \frac{6}{\pi^2} \simeq 0.6079 \end{aligned} \]

To make this argument precise, we define \(E_N:= \{1 \le m,n \le N \,: \mathrm{gcd}(m,n)=1\}\), \(S(N):= |E_N|\). Then \(q_N=S(N)/N^2\). However \[ S(N):= \sum_{1 \le m,n \le N : \mathrm{gcd}(m,n)=1} 1 = \sum_{d \le N} \mu(d) \left\lfloor \frac{N}{d} \right \rfloor^2 \] where the Möbius function \(\mu(d)\) satisfies \[ \sum_{d} \mu(d) d^{-s} = 1 / \zeta(s) \] Therefore we set \(\varepsilon_N:= q_N - 6/\pi^2\) and we want to show that \(\varepsilon_N\to 0\). Indeed from the above discussion \[ \varepsilon_N= \sum_{d \le N} \mu(d) \frac{1}{N^2} \left\lfloor \frac{N}{d} \right\rfloor^2 - \sum_{d} \mu(d) d{-2} \] which readily vanishes as \(N\to \infty\). One can indeed prove that, for \(N\ge N_0\) large enough and for some constants \(c_{\pm}>0\) \[ c_- \sqrt{\log \log N}/N \le \varepsilon_N \le c_+ \sqrt{\log \log N}/N \]

Additional Exercises

Exercise 17, Difficulty 2

\(200\) Probability students are divided into three groups of \(50\), \(50\), and \(100\) students each, to attend seminars in classrooms with the corresponding capacity.

- In how many ways can these groups of students be formed?

Alexandra and Svetlana are good friends and would like to be in the same room during the seminar. But they cannot stand Alexey, and they hope he will be assigned to a different room.

- What is the probability that their wishes are fulfilled?

This simple exercise is just to recall that sometimes there are several different natural probability spaces where one can calculate.

There are \(\binom{200}{50,50,100}\) ways to arrange the students in the three classrooms. However, if we consider the ways to divide the students in two groups of \(50\) and one group of \(100\), then we have \(\binom{200}{50,50,100}/2!\) arrangements.

There are \(\binom{197}{48,50,99}\) ways to arrange the students so that Alexandra and Svetlana are in the first room and Alexey in the third room, etc. Thus the required probability is \[ \frac{2\binom{197}{48,50,99}+2\binom{197}{48,49,100}+2\binom{197}{49,50,98}}{\binom{200}{50,50,100}} \simeq 0.219 \]

Notice that we could equivalently have reasoned by arranging students in groups (not distinguishing the two groups of \(50\)) instead of classrooms, which would have given us (of course it is the same) \[ \frac{\binom{197}{48,50,99}+\binom{197}{48,49,100}+\binom{197}{49,50,98}}{\binom{200}{50,50,100}/2!} \]

Exercise 18, Difficulty 5

An urn contains \(u_1\) balls of color \(1\), \(u_2\) balls of color \(2\), …, \(u_R\) balls of color \(R\). We perform \(n\) random draws, and immediately after each draw, the ball is returned to the urn along with \(m\) other balls of the same color (\(m\ge -1\) and \(n\le u_1+\ldots+ u_R\) if \(m=-1\)).

- What is the probability that a ball of color \(r\) will be drawn on the \(i\)-th draw?

- What is the probability that among the \(n\) selected balls, color \(1\) appears \(j_1\) times, color \(2\) appears \(j_2\) times, \(\ldots\), color \(R\) appears \(j_R\) times?

- Let \(u_1=u_2=\ldots=u_R=m\). Calculate the previous probability in the following cases: \(m=-1\) (drawing balls without replacement); \(m=0\) (drawing balls with replacement).

The probability of drawing a ball of color \(r\) on any specific draw \(i\) is \(u_r/U\), where \(U = \sum_r u_r\). Indeed the probability of a sequence of colors is independent of the sequence order.

For a specific sequence of draws with counts \(j_1, \dots, j_R\), the probability is: \[ P(\text{sequence}) = \frac{\prod_{r=1}^R \prod_{i=0}^{j_r-1}(u_r+im)}{\prod_{i=0}^{n-1}(U+im)} \] Since any sequence with the same counts has the same probability, the total probability is this value multiplied by the number of such sequences, \(\binom{n}{j_1, \dots, j_R}\): \[ P(j_1, \ldots, j_R) = \binom{n}{j_1, \dots, j_R} \frac{\prod_{r=1}^R \prod_{i=0}^{j_r-1}(u_r+im)}{\prod_{i=0}^{n-1}(U+im)} \]

-

Let \(u_r = u\) for all \(r\). So \(U=Ru\).

- \(m=0\) (drawing with replacement): This gives the multinomial distribution. \[ P(j_1, \ldots, j_R) = \binom{n}{j_1, \dots, j_R} \frac{\prod_{r=1}^R u^{j_r}}{(Ru)^n} = \binom{n}{j_1, \dots, j_R} \frac{u^n}{R^n u^n} = \binom{n}{j_1, \dots, j_R} (1/R)^n \]

- \(m=-1\) (drawing without replacement): This gives the multivariate hypergeometric distribution. \[ P(j_1, \ldots, j_R) = \frac{\binom{u}{j_1}\binom{u}{j_2}\cdots\binom{u}{j_R}}{\binom{Ru}{n}} \]